Electricity Comes to the Farm

Electricity Comes to the Farm

Click Images To Enlarge

Electricity Comes to Rural Marathon County

Nationwide, the electric industry began developing in the late 1880s. Early urban electric companies mainly powered street railway systems that provided in-town (trolley) transportation. There were also companies that manufactured gas from coal but it was only used for lighting, not for providing any type of power. With the merging of many of these electric and gas companies, towns had a reliable source of electricity for both illumination and power.

Nationwide, the electric industry began developing in the late 1880s. Early urban electric companies mainly powered street railway systems that provided in-town (trolley) transportation. There were also companies that manufactured gas from coal but it was only used for lighting, not for providing any type of power. With the merging of many of these electric and gas companies, towns had a reliable source of electricity for both illumination and power.

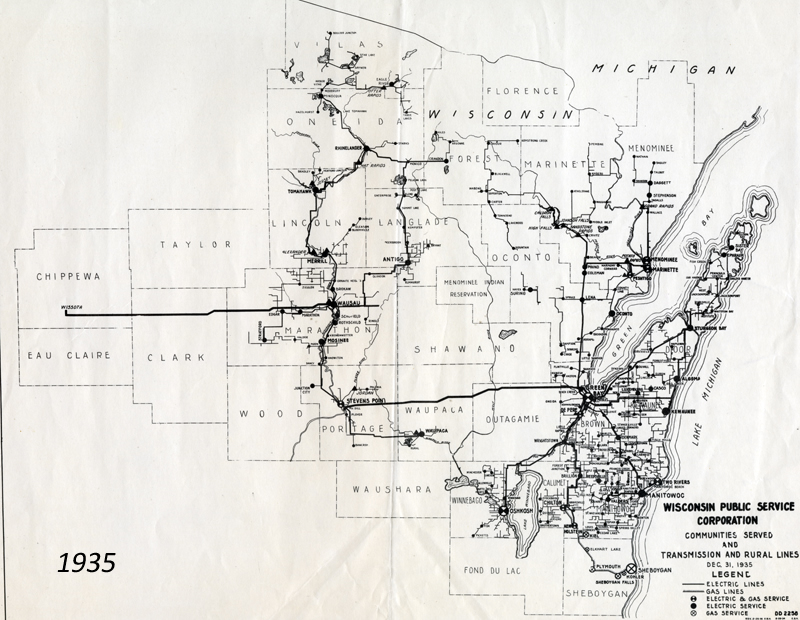

In 1915 in Wausau, the Wisconsin Valley Electric Company emerged as the successor to two previous electric companies and a street railway company. It continued to grow and by 1927 had become a large company that also served many other central and northern Wisconsin towns. In 1933, it merged with Wisconsin Public Service.

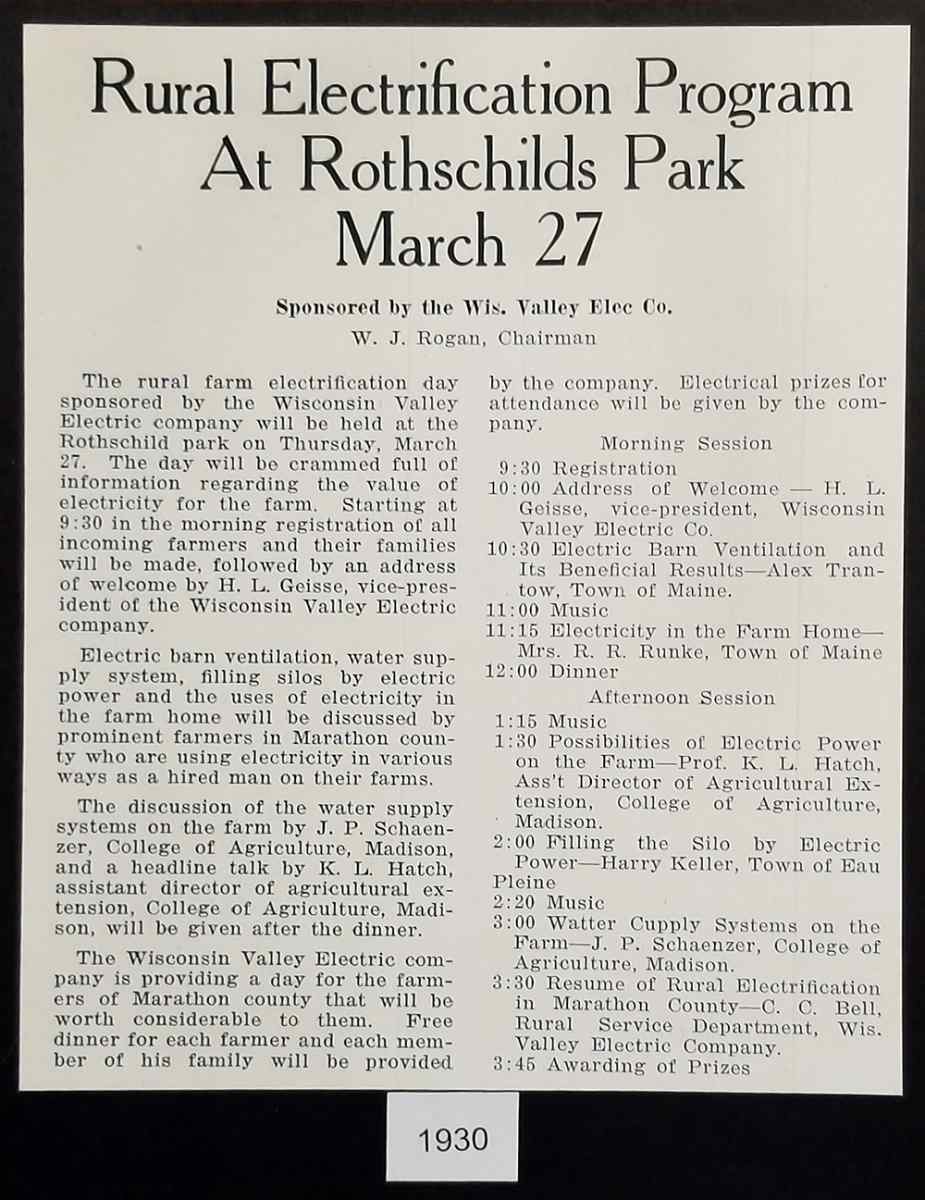

While many populated areas of Marathon County were served by private electric companies, such as Wisconsin Public Service or Northern States Power, the majority of rural residents (about 75%) were still without electricity in 1930. There were small pockets of homes and farms powered by local sawmills or other businesses that generated their own electricity and sold it to their neighbors. Some families were able to afford in-home battery plants, where a gas motor charged a bank of batteries that provided limited power, but they could be costly to buy.

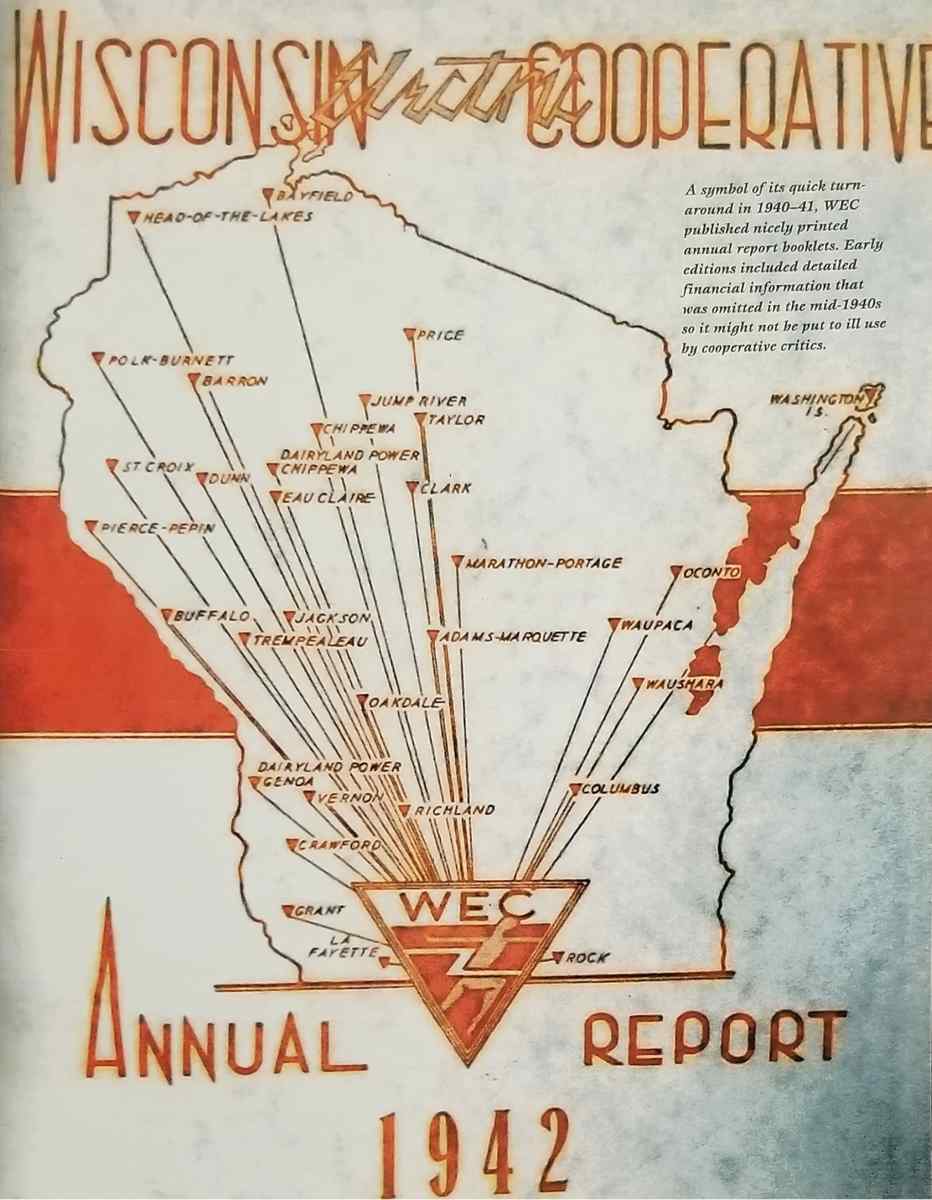

During the 1930s, after the creation of the Rural Electrification Administration, many cooperatives were formed by farmers to bring electricity to rural areas. In Wisconsin, farmer-owned co-ops were already a prominent factor in agriculture, including operating creameries and cheese factories, so forming electrical co-ops was a natural response to the need for electricity. Rural areas in southern, western and southeast Marathon County were initially served by several co-ops including the Marathon-Portage Electric Cooperative, Clark Electric Cooperative, Waupaca Electric Cooperative and Taylor Electric Cooperative. All remain in business today, although Marathon-Portage merged with with Waupaca Electric in 1947 to form the Central Wisconsin Electric Cooperative.

Rural residents outside the service area of an electric co-op, private electric utility or other provider remained in the dark for decades.

The Rural Electrification Administration and Its Impact

When Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president of the United States in 1932, he was already a champion of rural electrification. During the 1920s he spent much of his time in rural Georgia receiving treatment for polio at thermal springs and he observed the poverty of rural Americans living without electricity or running water. Later, as a New York state senator and governor, he promoted affordable electricity for everyone.

When Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president of the United States in 1932, he was already a champion of rural electrification. During the 1920s he spent much of his time in rural Georgia receiving treatment for polio at thermal springs and he observed the poverty of rural Americans living without electricity or running water. Later, as a New York state senator and governor, he promoted affordable electricity for everyone.

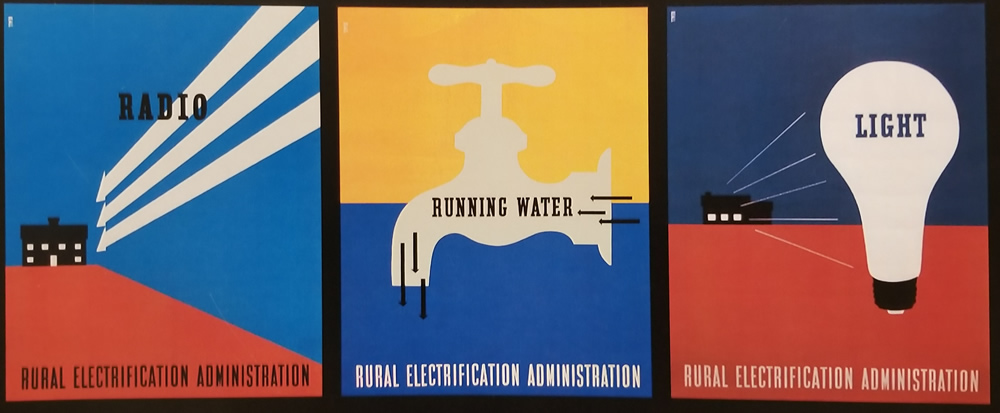

On May 11, 1935 Roosevelt signed an executive order creating the Rural Electrification Administration, whose purpose was to initiate and administer projects “with respect to the generation, transmission and distribution of electric energy in rural areas”. The REA became a permanent government agency in 1936 and, through the Rural Electrification Act, was authorized to issue low-interest loans for funding rural electrification projects.

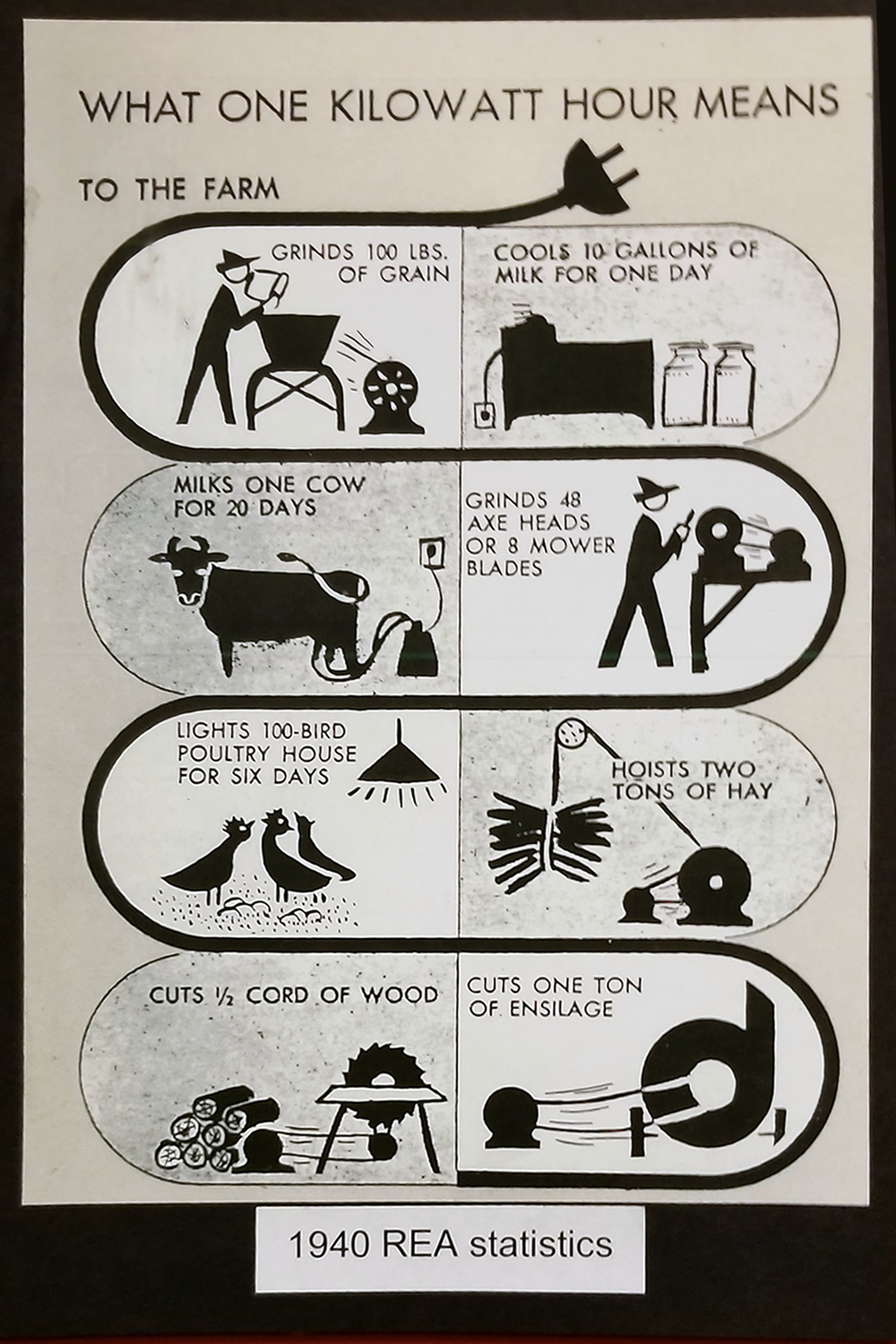

REA engineers came up with innovations to make electrifying the countryside less expensive. High-strength conductors permitted longer spans of wires, reducing the number of poles per mile, and poles became both lighter and stronger. The engineers also developed more efficient installation procedures for the utility crews. By 1939 the average national cost of constructing a mile of rural electric line had come down from over $2,000 to only $600.

Educating consumers about the uses of electricity was also an important function of the REA in its early years. The agency created the “Farm Equipment Tour” which went on the road with a circus tent and trucks loaded with demonstration equipment for farm and home. Manufacturers of electrical equipment joined the show and farmers flocked to see the benefits of electrification. Women, in particular, were excited about the myriad of time and labor savings devices that would be available to them when their homes were electrified.

The REA did more to bring farmers into the 20th century than any other single act. Thanks to the REA, seven out of 10 farms were electrified by 1950, compared to one out of 10 in 1935.

Rural Electric Cooperatives Formed

Private electric utility companies in the 1930s were reluctant to use REA loans to bring lines to rural areas, as it was considerably more costly than providing electricity to cities and towns. This led to the formation of rural electric cooperatives across the country.

Private electric utility companies in the 1930s were reluctant to use REA loans to bring lines to rural areas, as it was considerably more costly than providing electricity to cities and towns. This led to the formation of rural electric cooperatives across the country.

Forming a co-op was not an easy task. Farmers needed to enroll as many neighbors as they could into the co-op, then plan the path of the proposed electric lines and obtain easements across affected properties. In some cases, private electric companies came into a co-op’s service area after all the organization had been done and installed power lines through the most profitable areas of the co-ops proposed territory, sometimes in the middle of the night.

In the early 1940s, during World War II, the REA convinced the War Production Board that electrified farms dramatically increased food production. This allowed them to continue providing loans, though the progress of electrification had slowed due to wartime shortages of copper and other critical supplies. By the end of the war more than 50% of the nation’s farms were still without electric power but demand was at an all-time high. Returning veterans, now familiar with the benefits of electricity, wanted it on their farms.

In 1947, Congress appropriated more funds for the REA and line construction moved swiftly across rural America. By 1950 more than 75% of American farms were electrified. By 1960, 96% of American farms were connected to electricity.

Rural electrification had a dramatic impact on the lives of those whose homes and farms were hooked up to power lines - it brought them into the 20th century. Having light in the house at night changed the way the entire family lived. Household chores were revolutionized. Electric pumps and heat provided hot and cold running water; electric stoves, refrigerators and freezers made food preparation and storage easier. Many appliances, from sewing machines to washing machines, improved the life of the rural housewife. Farming activities also greatly benefited from electricity. Electric milking machines and milk coolers made a significant impact on dairy farm while electric motors made hundreds of jobs easier, from sawing wood to filling the silo and hatching chickens. Few families purchased all of these items at once, but as money became available they were added one by one. The most popular first purchases for the home were radios and electric irons.

"Spite Lines" Abound

In the early years of the efforts for rural electrification, private investor- owned electric utilities had little interest in bringing service to rural areas. They saw no opportunity to make money by stringing miles of line between distant farms. Instead they concentrated on more urban areas that had dozens or hundreds of home and businesses per square mile, instead of the handful of farms per square mile.

In the early years of the efforts for rural electrification, private investor- owned electric utilities had little interest in bringing service to rural areas. They saw no opportunity to make money by stringing miles of line between distant farms. Instead they concentrated on more urban areas that had dozens or hundreds of home and businesses per square mile, instead of the handful of farms per square mile.

When it became apparent that there was a profitable rural market, competition began with the developing local electric cooperatives. Private utilities began taking over the more populated, and thereby more profitable, rural areas for their business, even if a co-op was already committed to serving those customers. These lines, sometimes set during the middle of the night, were referred to as “spite lines”.

The 1937 Rush Act curbed spite lines by allowing co-ops to protect their areas by filing a proposed service map with the Public Service Commission.

The Marathon-Portage Electric Cooperative

The beginning...and the end

In September 1940 a group of men from Mosinee, Hatley, Wittenberg, Knowlton, Schofield, Stevens Point and Custer organized the Marathon-Portage Electric Cooperative for the purpose of providing affordable electric service to their rural communities. During the next two months, 162 membership applications were received and by February 1941 the number had swelled to 355, covering 181 miles of rural electric lines.

Even with this progress, talks of merging with the nearby Waupaca Electric Cooperative had started in early 1941 but were soon dismissed by the Rural Electric Administration as being a threat to the expansion of electric service in Marathon County. Copper shortages brought on by World War II and the withdrawal of a $190,000 REA loan for the duration of the war essentially stopped all projects planned by the Marathon-Portage co-op.

In 1943 a private electric utility company, somehow undeterred by wartime shortages of materials, began pilfering large parts of the co-op’s territory by luring away their most profitable potential customers. After several years of hearings, attempted compromise and offers to sell the “stolen” lines back to the co-op, talks between the two factions collapsed.

Despite this battle, from 1945 to 1947 the Marathon-Portage co-op was able to construct electric lines serving 412 farms, homes and businesses covering 205 miles of line. But the damage had already been done, by world events and unfair competition. In 1947 the Marathon-Portage Electric Cooperative merged with the Waupaca Electric Cooperative to form the Central Wisconsin Electric Cooperative, which remains in business 80 years later.

Wisconsin Valley Electric Company & Wisconsin Public Service

On May 31, 1883 the first electric light in Wausau was powered by a privately-owned dynamo at the Leahy and Beebe sawmill. Two months later the Wausau Electric Light and Power Company was incorporated. The first commercial building illuminated in Wausau, the downtown Bee Hive Store, was lit in December 1883. Electricity took hold and quickly spread through businesses and residential neighborhoods in Wausau. Later a second utility, the Wausau Electric Light Company, was formed.

On May 31, 1883 the first electric light in Wausau was powered by a privately-owned dynamo at the Leahy and Beebe sawmill. Two months later the Wausau Electric Light and Power Company was incorporated. The first commercial building illuminated in Wausau, the downtown Bee Hive Store, was lit in December 1883. Electricity took hold and quickly spread through businesses and residential neighborhoods in Wausau. Later a second utility, the Wausau Electric Light Company, was formed.

Having enjoyed the benefits of electricity for over two decades, in 1906 a group of businessmen formed the Wisconsin Street Railway Company, which provided electric trolley service between Wausau, Schofield and Rothschild. Railroad management, convinced that joint ownership of the electric utility and railroad companies would increase both efficiency and profits, acquired the electric utility and, in 1915, changed the name to Wisconsin Valley Electric Company.

The roots of Wisconsin Public Service are traced to the Oshkosh Gas Light Company, which began electric service in 1885. Having already provided gas for lighting, the company became the first combined gas and electric company. After the company was sold in 1922, the name was changed to Wisconsin Public Service Corporation. Over the next ten years the company experienced tremendous growth through a series of acquisitions, mergers and expansions and their service territory expanded considerably throughout northeastern Wisconsin.

The roots of Wisconsin Public Service are traced to the Oshkosh Gas Light Company, which began electric service in 1885. Having already provided gas for lighting, the company became the first combined gas and electric company. After the company was sold in 1922, the name was changed to Wisconsin Public Service Corporation. Over the next ten years the company experienced tremendous growth through a series of acquisitions, mergers and expansions and their service territory expanded considerably throughout northeastern Wisconsin.

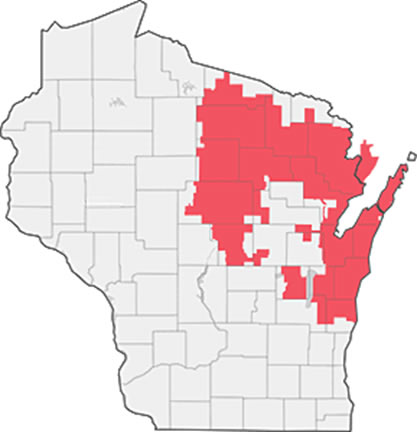

On June 5, 1933 Wisconsin Valley Electric Company merged with Wisconsin Public Service. Wisconsin Public Service currently serves more than 450,000 electric customers and more than 326,000 natural gas customers in northeast and central Wisconsin and an adjacent portion of Upper Michigan.

The Cost of Electricity

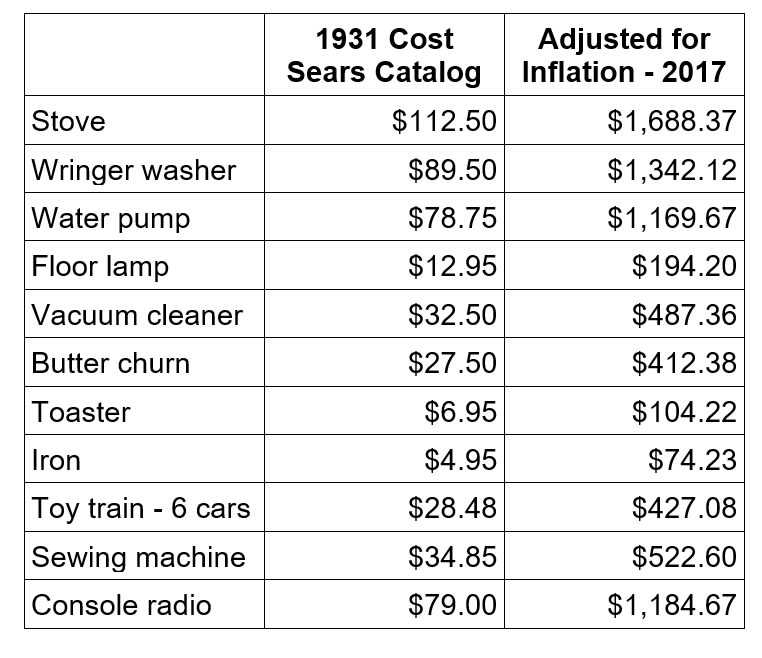

It’s easy to believe that families quickly acquired the most modern appliances and devices when electricity became available in rural areas. In reality, the primary reason for hooking up to the “high-line” often was to electrify a barn or replace hand-operated machinery, such as water pumps and tools, with their electric counterpart.  Refrigerators, radios and electric stoves were considered luxury items and may not have been added to the household for many years. Some housewifes treated themselves to an electric iron or sewing machine, which helped to lessen their daily drudgery.

Refrigerators, radios and electric stoves were considered luxury items and may not have been added to the household for many years. Some housewifes treated themselves to an electric iron or sewing machine, which helped to lessen their daily drudgery.

According to the the Wisconsin Agricultural Statistics Service, the average gross income for Marathon County farmers in 1933 was $905 per year or about $75 per month. The initial expense of bringing wires from the road to the house, wiring the house and barn, and installing light fixtures and outlets was a monumental financial outlay. Once service was installed, families needed to decide which appliances and devices were most important to acquire.

The 1931 Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalog lists the prices shown on this chart for electric devices - we’ve added what the comparable cost would be in 2017, after adjusting for inflation. Adjusting 1933 farm income for inflation equates to an annual income of $13,571 in 2017, which is slightly above the poverty guideline for a single person.