Knowlton's Twin Bridges

In 1978 the Marathon County Highway Committee had a problem. The Highway 34 Bridge over Lake Du Bay had just received the dubious honor of the oldest and narrowest trunk highway bridge in the State of Wisconsin. This was perhaps symptomatic of a larger issue as Wisconsin was having issues maintaining its highway bridges and overpasses at this point in history. With 1,419 bridges and overpasses listed as critically deficient Wisconsin ranked number seven for worst maintained bridges in the country.1 County Highway Commissioner Calvin E. Cook had this to say of the Knowlton Bridge: “ [The Highway Committee] is especially concerned with regards to the Knowlton Bridge on STH 34. [It] is actually a wooden horse-and-buggy later addition to a railway bridge erected about 1894.” Commissioner Cook went on to state that not only was this likely the oldest highway bridge in the state but at only ten feet wide and a single lane it was by far the narrowest as well.2 This was not the image that Marathon County wanted to present.

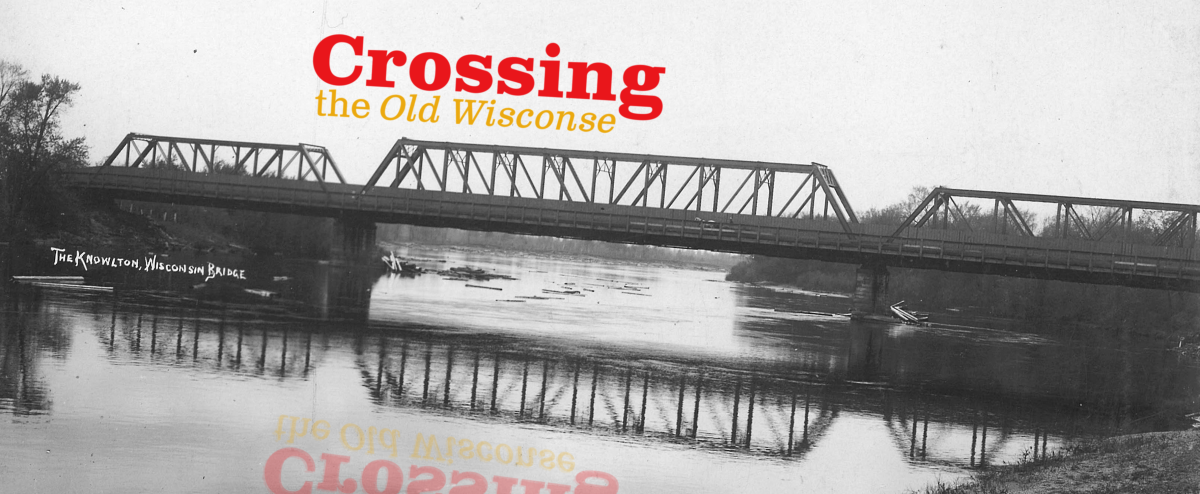

The Infamous Combined Bridge over Lake Du Bay pictured sometime in the 1960s or 70s.

Credit: MCHS Photo Collection

Humble Beginings

In 1874, the Wisconsin Valley Railroad's line reached Marathon County. Shortly thereafter a bridge, known as Wisconsin Valley Railroad Bridge G-276, was erected to carry the line into Wausau. As part of the railroad’s agreement with the county this bridge was to be made open to foot and wagon traffic as well as to trains. To satisfy the agreement the railroad opted not to build a proper road deck and instead simply laid planks on either side of the rails giving just enough room for wagon wheels to run or a careful pedestrian to walk.3 It wasn't much but it was better than nothing at all. While almost unheard of in the 21st century, combined bridges like this one were not unheard of in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and in a rural setting like Marathon County the arrangement would not have caused much of an issue. So, the bridge in its first configuration was not unusual given its time and place but it set a precedent for a combined bridge at that location.

New Bridge Old Promises

In 1894, the bridge, now owned by the Chicago Milwaukee & St. Paul railroad, was in need of replacement. When the railroad approached the county about replacing the bridge they were reminded of their predecessor’s agreement and informed that the new bridge would also have to be dual use.4 The new bridge was at first glance unremarkable; a steel Pratt Truss, it looked exactly like any other railroad bridge except for the fact that a road bridge ran right next to it. In actuality the road bridge wasn’t next to the railroad bridge, it was cantilevered off of it. In a scheme that would have made Frank Lloyd Wright jealous, a series of hefty wooden beams were bolted to the bottom chord of the railroad bridge, and the road bridge built on top of them.5

The new bridge met with criticism. Some believed that it would be unable to support the combined weight of a train and road traffic and while this proved untrue, the novel design of the new bridge presented several problems. Crossing the bridge while a train approached from the opposite direction was disorienting and, as cars came into use this occasionally led to accidents. To solve this problem a wooden barrier, which can be seen in most pictures of the bridge, was erected to block trains from view.6 The barrier also helped with, though didn’t totally eliminate, the problem of dragging equipment or freight striking passing vehicles and pedestrians. A train at speed could easily turn a wayward pulp log or length of chain into a deadly missile and even if everything was properly secured pulpwood logs would occasionally strike the trusswork of the bridge, showering passersby with splinters or even entire logs. Upon approaching the bridge, crews were required to stop their trains and conduct an inspection of all cars before proceeding at a walking pace. The process took upwards of half an hour and was, understandably, not at all popular with train crews.7 It is no wonder then that the bridge was regarded with caution and distrust by locals and railroaders alike.

The fence blocking passing trains (and hopefully any debris) from view can be seen on the right.

Credit: MCHS Photo Collection

Modernizing

In 1936, The Milwaukee Road, tired of the constant inconvenience and danger caused by the bridge, surveyed the site for a replacement.8 That should have been the end of the story but the Milwaukee Road in the grips of the Great Depression, and having filed for bankruptcy the prior year, couldn’t muster the necessary funds. The War Years brought deferred maintenance followed by a postwar decline in the railroad industry as a whole. Replacing a minor bridge like G-276 was far from a priority for the struggling railroad and so it was left in place. Replacement of the road portion of the bridge was also a low priority; with long-distance travelers preferring to take the more direct U.S. 51, STH 34 saw mostly local traffic.9

Highways proved only a temporary reprieve for bridge G-276. The 1960s and 70s saw increasing commuter traffic on STH 34 and increased complaints about the inadequacy of the bridge.10 At ten feet wide G-276 was limited to serving only one direction of traffic at a time at a speed of fifteen miles per hour and because of its wooden cantilever construction heavier vehicles were unable to cross at all and were forced to detour through Stevens Point. The railroad portion of the structure was becoming inadequate as well. In 1960, the Weston Generating Station brought a new unit online; the resulting increase in coal train traffic to the station prompting The Milwaukee Road to once again consider and then back out of replacing the bridge.11

A CN Train crosses the new rail only Knowlton Bridge.

Credit: Brian Wiggins

In 1979, The Milwaukee Road announced it would be replacing bridge G-276 with a new rail-only bridge that year.12 The Weston Generating Station had just debuted its Weston III Unit which, when it came online in 1981, was projected to require an extra 240 carloads of coal per week13 on top of the already massive coal trains that already threatened to overwhelm the aging bridge. The news that the new bridge would no longer handle road traffic prompted the DOT to fast-track its own replacement project and the road portion of the bridge closed to traffic in May of 1979.14 The new road bridge was opened to traffic on October 15, 1980.15 The new railroad bridge was begun shortly thereafter and by 1981 there was nothing left of what may have been the strangest bridge in Wisconsin.

< Previous Story Glossary Main Index

1. "Bridges and the Road Tax." Wausau Daily Herald (Wausau), January 10, 1972.

2. "Knowlton Bridge Problem." Wausau Daily Herald (Wausau), January 21, 1978.

3. Luedtke, Ben. "Cars, Train Share Bridge." Record Herald (Wausau), March 7, 1975.

4. "Cars, Train Share Bridge"

5. "Bridges and the Road Tax."

6. “Cars, Train Share Bridge”

7. "Cars, Train Share Bridge"

8. "Cars, Train Share Bridge"

9."Cars, Train Share Bridge"

10. “Knowlton Bridge Problem.”

11. "Work on Bridge May Begin in Spring." Wausau Daily Herald (Wausau), March 14, 1979.

12. "Work on Bridge May Begin in Spring"

13. Berger, Tom. "State of Railroads Poses Another Energy Problem." Wausau Daily Herald (Wausau), May 14, 1979.

14. "Knowlton Bridge Closed." Wausau Daily Herald (Wausau), May 5, 1979.

15. "Knowlton Bridge Open." Wausau Daily Herald (Wausau), October 15, 1980.