The Window Companies

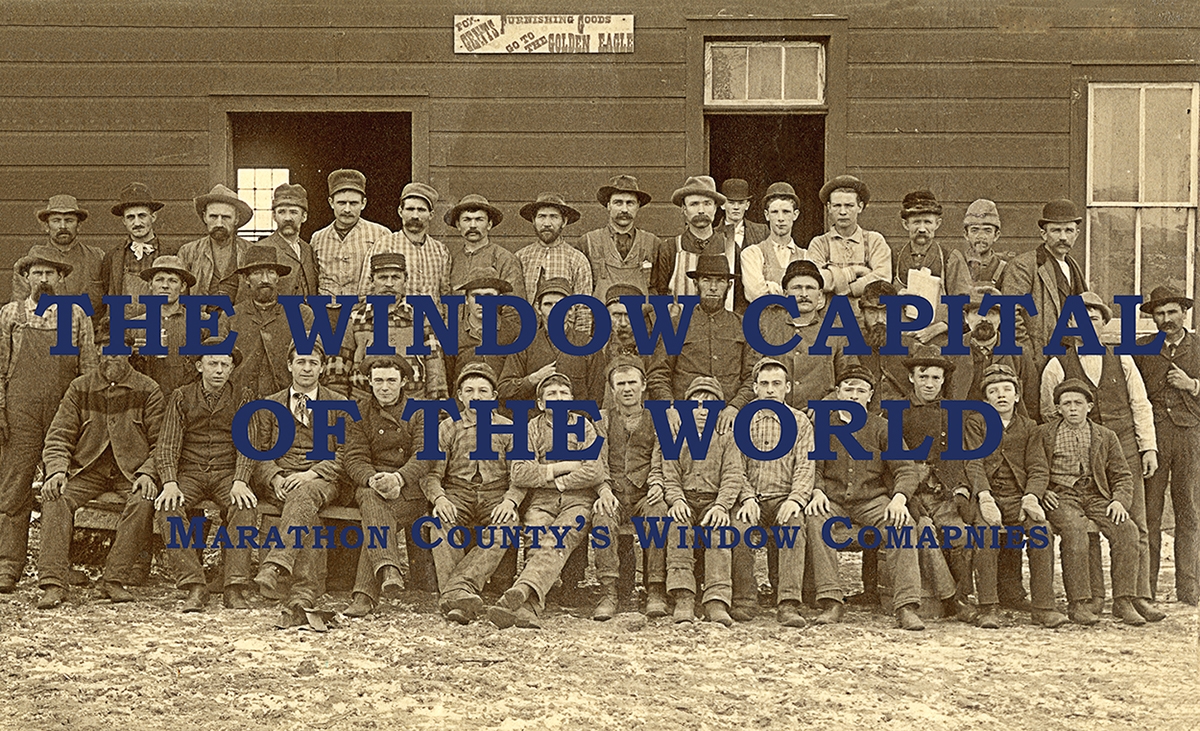

An Overview of the Window Companies of Marathon County

Wausau's claim to being the Window Capital of the World was built on nearly 150 years of window making here. From water-powered mills producing simple wood window sashes to mid-century ventures making state-of-the-art metal, architectural windows, and more; Marathon County has benefited from a long legacy of window expertise in the region.

This page gives an overview of the window over the history of its production here in Marathon County. It is included to put the individual companies and stories into a wider historical context. If you would prefer to start looking through the stories of specific companies, you can return to the main page, or use the navigation bar on the right (at the bottom for mobile users).

The Early Years

The early settlements of Central Wisconsin began as a collection of lumber camps, mills, and occasional subsistence farms. With the growth of the communities in the final decades of the nineteenth century, there was an increasing need for all the kinds of buildings that the communities needed to grow. And someone would need to make the windows for all of these buildings.

In these early years, competent carpenters were in high demand. Many people were capable of stacking hewn logs or putting up simple wood frames, but it was rare to find someone who could make a wood sash that were airtight and doors that swung snugly in their frames. And so when someone like George Werheim came to the area, he found steady work as a carpenter and joiner.

By the 1870s, this demand for quality, specialty wood products created opportunities for some of the first manufacturing operations in the region. By the turn of the century, a number of factories and millworks had been established in Wausau and other towns across Central Wisconsin, to produce wood window sashes and doors.

These early manufacturers were primarily producing window sashes and doors for the local area, not for regional (let alone national) markets. But over the course of the next half century, this would change, largely through the creation of standardized, branded window lines.

Standardization

Around the turn of the twentieth century, if you wanted to put some windows in a building, you would leave an opening in (or cut one into) the wall the size of the window you wanted. Then you would order window sashes to fit those openings from one of a local factory or millwork.

^ A progress photo taken during the construction Johnson House in Wausau. Note the holes left for the future installation of windows.

And since each building would need different openings for its new windows, the factories had to be able to quickly adapt to make a size and type of window from among hundreds or even thousands of combinations of sizes and styles. And because the companies could not know how many windows or what sizes those windows would need to be, they had to be completely reactive to the market.

This also meant number of jobs at a factory fluctuated along with building trends. A period with increased construction might mean hiring new workers to help keep up with new orders, while a sudden economic downturn might mean having to layoff or fire dozens of workers.

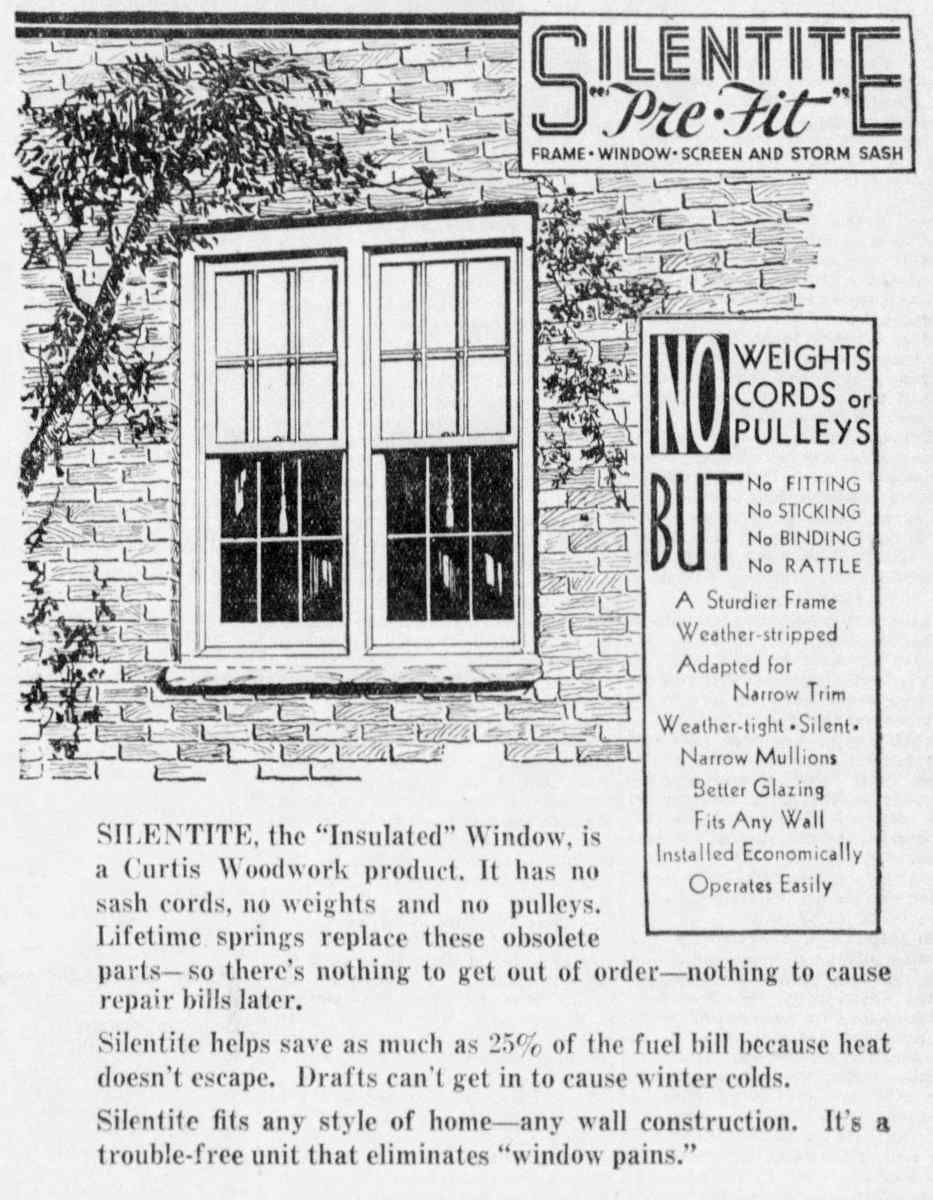

But by the 1930s, things were starting to change. Curtis & Yale had introduced their brand of "Silentite" windows, which were marketed as "pre-fit" windows. These modern windows included nearly everything you needed to put a functional and good looking window in a wall—in sizes that were a bit more standard.

Before these "all-in-one" type windows, at least a half dozen people had to be brought in to get a final window installed in a building. There were the builders who cut a hole in the wall for a window and the sash maker who manufactured the wood frame for the window. You also needed a glass-cutter to cut a sheet of glass to fit the opening and someone to glaze (or install) the panes of glass into the window sashes. And once the window was in the wall, you would need a carpenter to produce the molding to go around the frame, a painter to paint the wood frame and molding, and people to provide the latches, locks, hinges, screens, counter-weights, pulleys, and other bits of hardware necessary for a new window.

And so by using the all-in-one windows that the producers had made to "pre-fit" the space, the window installation process was simpler and cheaper in the long run.

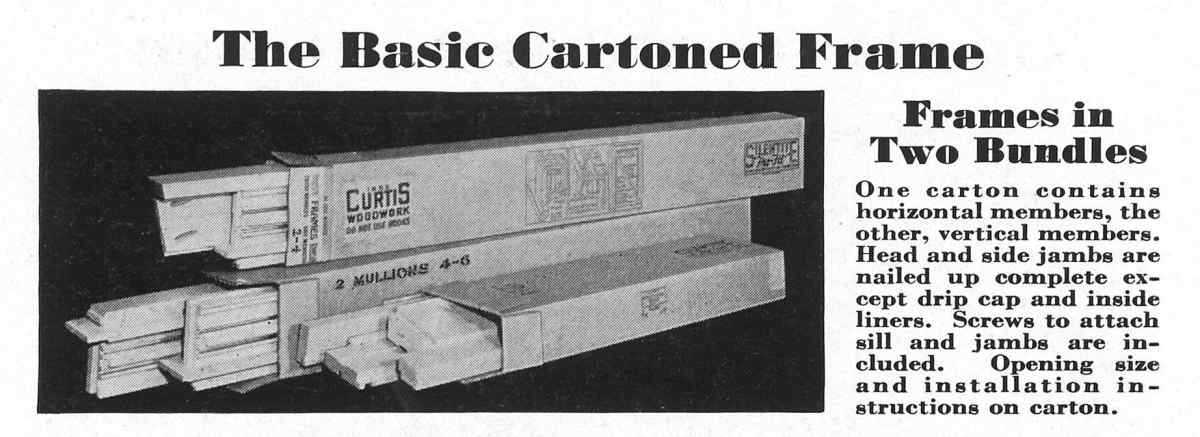

^ The Silentite windows shipped to the customer in cartons, from a mid 1940s Curtis product catalog.

Consumers were assured that "it will be seen that this unit idea does not preclude a wide range of choice because a frame is provided for every type of wall construction and in all commonly used sizes." But by focusing efforts on these more standardized, prefabricated window sashes, these companies were able to grow their businesses beyond their previously local scale to reach regional markets.

Catch Up Modernization

While this standardization was a gradual process for Curtis over the years, it was more sudden for local manufacturers that only underwent modernization after they were purchased by new owners in the mid 1940s:

The Usow/Cohans took over the old J.M. Kuebler Factory in 1945, and found it lagging far behind what would be expected of a wood manufacturer of the mid century. After a decade of modernization—including making both updates to the facilities and standardizing the product catalogs—the company emerged as an influential company within the industry. And to mark the shift toward a modern company, it shed its old name (J.M. Kuebler Company) in favor of Marathon Millwork.

Similarly in 1946, the George Silbernagel & Sons Company was purchased by the Harris Brothers of Chicago. The new owners quickly shifted to adopt a new name (Silcrest) and started the process of standardizing the product lines. After a few years, the entire company adopted the new name Crestline (taken from their popular line of woodwork), and along with the name change, the company underwent the same modernization process seen at Kuebler/Marathon Millwork and Curtis.

Both Marathon Millwork and Crestline found a place in a wood window industry in the mid twentieth century. Both were also expanding to sell their windows to new markets, through the creation of a distinct brand name that was sold through a network of distributors. By developing contacts in retail and building supply stores, Crestline, Marathon Millwork, and Curtis brand windows produced in Wausau ended up in buildings across North America.

^ The big three wood window manufacturers of Wausau in the 1950s and early 1960s.

And so by the mid twentieth century, there were three major wood window makers here in Marathon County. The next few decades would see the decline of Curtis (1962) and Marathon Millwork (1972), radical restructuring of Crestline as part of SNE (1981), and the rise of a new contender called Kolbe & Kolbe (as well as less successful startups like Vanguard).

New Developments in Windows

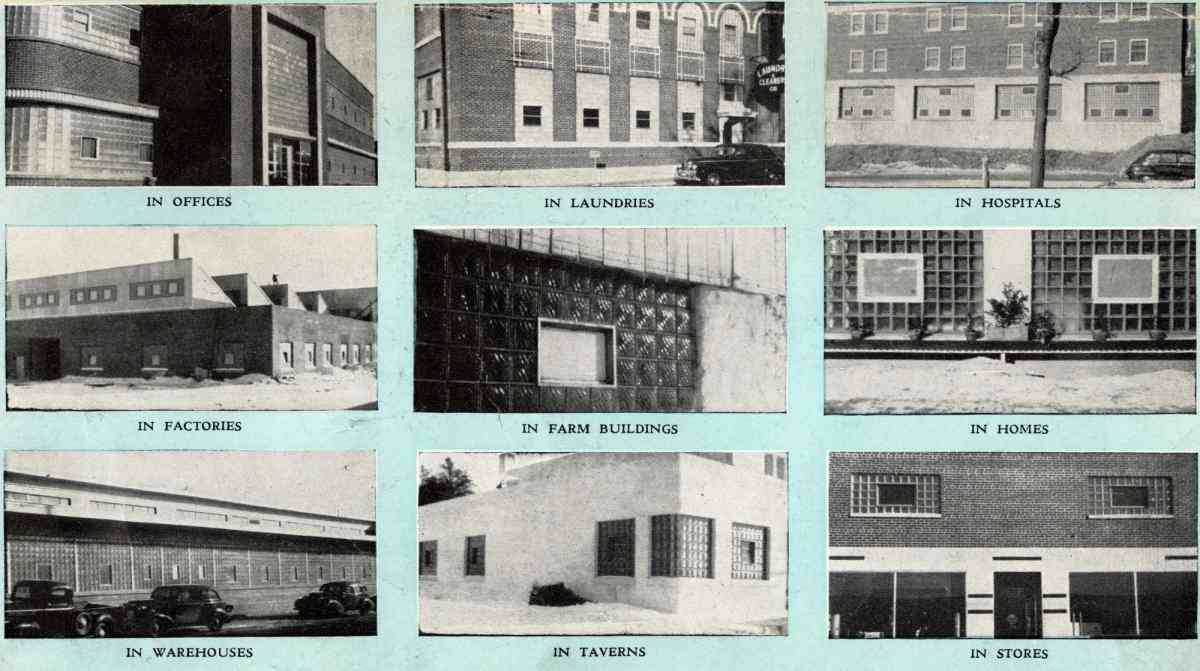

But while Marathon Millwork and Crestline were still being retooled by their new owners in the 1940s, new options for windows were emerging as popular alternatives to the traditional wood window sash. And although these trends emerged from the poplar glass block walls, they would soon be changing the architectural landscape across the world.

Building on the Glass Block

In the 1930s, the glass block had emerged as a popular building material for all sorts of buildings. The Owens-Illinois Glass Company of Ohio had developed a way to produce the blocks of glass with one side hollowed out to provide a pocket of air inside.

The strength of the glass block allowed for larger portions of a wall to be given over to "windows," and the larger surface-area allowed for more light to get from outside to the inside of a building. The solid construction of glass block walls did limit the visibility through them, and so they were typically not used as windows for commercial storefronts or the main rooms of residential homes. But glass blocks were perfect for industrial, commercial, and institutional buildings were you wanted to maximize the amount of natural light inside without needing to see in or out of the structure.

^ Wausau Laundry and Cleaners Co. was one of many buildings in the mid twentieth century to include the glass block wall. From the Becker-Geisel Collection, MCHS.

Glass blocks also were also much better at being keeping heat from passing from inside to outside (or vice versa). The air pocket helped insulate the layers of glass. So for heat to pass through the glass block, it would have to warm up one layer of glass, then the air pocket, then the second layer of glass, before it could pass inside the building.

For all these reasons (as well as their thoroughly modernist look), the glass block became popular across the United States. And as people in Central Wisconsin adopted the glass blocks in new buildings (from everything from cow barns, to junior high schools, paper factories, and bowling alleys), some realized there was an opportunity for a new product born out of the biggest drawback to the new kind of window. Glass block walls posed a problem for health and safety, as they could not be opened for ventilation or to provide an escape (i.e. in the case of a fire). And so a number of companies were established in Marathon county to produce ventilators for glass block walls.

^ Various examples of Marmet's glass block ventilators

Anton Hoffer, founder Hoffer Glass, the popular chain of building supply stores that sold glass blocks, created Marmet in 1946 to produce these glass block ventilators. A decade later, a group of Marmet employees left to start Wausau Metals to do the same. These glass block ventilators were original produced from steel, but quickly aluminum became the prefered medium for the frames.

By the late 1950s, aluminum window companies had developed new techniques in making windows that were integrated into the walls themselves. Just as the glass blocks had before them, these new models were successful in integrating the windows into the walls of buildings, which fundamentally changed the way some buildings were constructed.

Both Marmet and Wausau metals would begin on the foundation of making glass block ventilators, before expanding to produce other kinds of aluminum windows, and eventually arriving on making window-walls, curtain-walls, and similar integrated, window-wall systems.

Window-Wall Systems

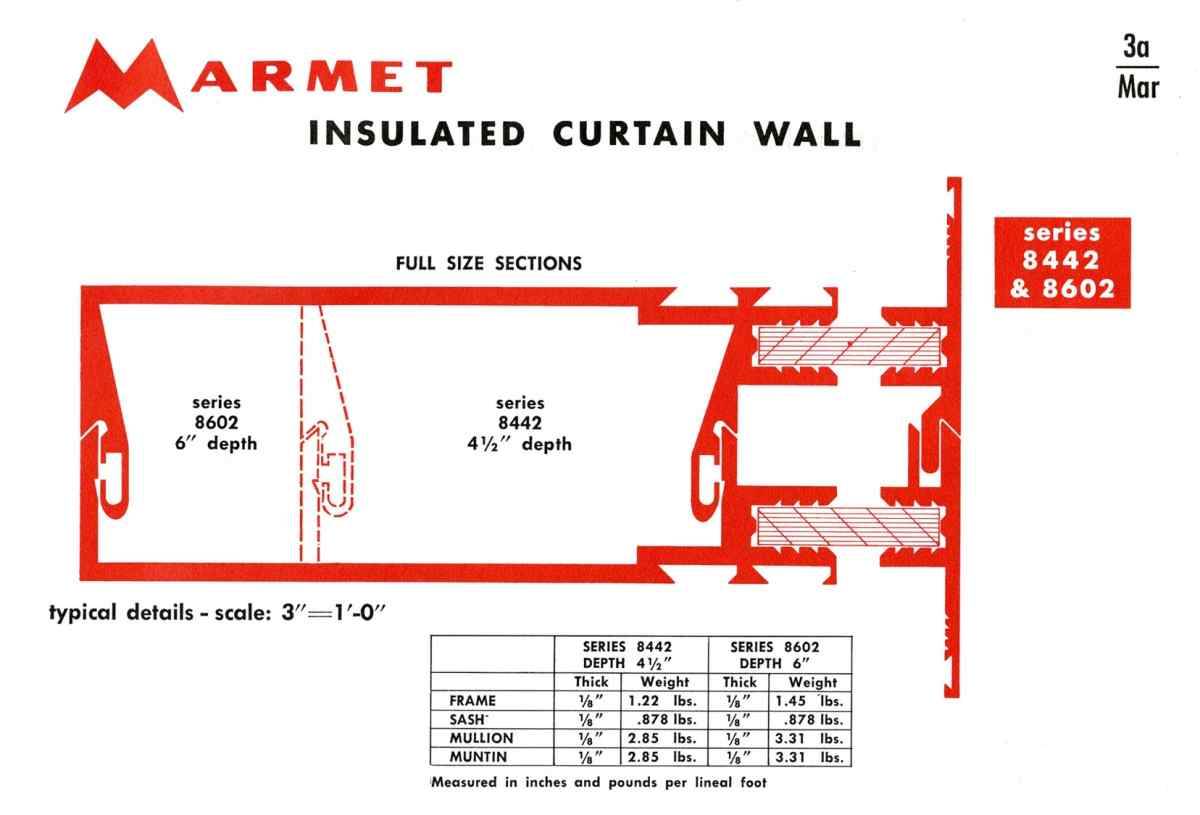

Aluminum extrusion proved to be a highly flexible way of making building components. In the late 1950s, Marmet patented the "insu-wall," which used aluminum extrusions to create joining points for wall panels. Before long the insu-wall was being used to include aluminum window inserts as well as wall panels in an integrated window-wall system.

^ Cutout diagram of Marmet's "Insu-Wall", from a brochure published in 1961 or 1962.

Just as the glass block walls had revolutionized the design of buildings by blurring the distinction between windows and walls, these new systems based largely on aluminum extrusions were doing the same.

In the above comparison, showing two Wausau bank buildings built 50 years apart, illustrates this well. Both buildings were built by the same bank (although the name has changed a few times over the years) on Wausau's Third Street,

The American National Bank on the left was built in 1925, and was designed to have as many windows as possible in the walls to maximize the amount of light brought inside. But these windows were "punch-outs," whereby the windows were installed into spaces left into the wall. And so the building could only accommodate so many windows before the structure would become unstable.

By the time First American Center was build in 1975, the window-wall system had become well established, with the result that the windows were designed as integrated part of the walls. In this case, ribbon windows provided structural support while also allowing the glass to stretch across the entire length of the building.

Pushing Architectural Windows Further

Over the last 70 years since the introduction of the Insu-Wall, just about every part of the window has seen further development. The metal windows produced by Marmet, Wausau Metals, and a handful of new companies that emerged in the subsequent decades (including Milco, Modu-Line, Mid Wisconsin Manufacturing, Republic-AMS, Inc., and Engineered Curtainwall), changed with the times to adopt new developments. In many cases these changes were integrated into new generations of their windows by their engineers.

For example, many of the windows produced by Marathon County's architectural window makers came to have more than one glazing; or panes of glass in the window. Just as the pocket of air in the glass blocks had created an efficient temperature barrier, extra panes of glass in metal windows isolated the parts of the window to minimize the transfer of heat from one part to another. One layer of glass would need to heat up to the point it could influence the temperature of the pocket of air, which in turn would have to become warm enough to raise the temperature of the next layer of glass, and so on.

^ Looking out from the lobby of the Wausau Airport. The rising popularity of metal windows also came with the wide-scale adoption of climate control systems like air conditioning. So having energy efficient windows were important for not only keeping out the conditions outside, but also keeping the desired temperature inside a building.

Other developments in the architectural metal windows need the creation of other businesses to provide specialized services that it was not possible (or financially viable) for the metal window makers to do themselves. Companies like Custom Glass Products provided glass processing services that includes applying low-e coating (which helps to reflect the parts of sunlight that contain heat and UV rays away from a building while letting in visible light). A company might turn to Rib Mountain Glass to helps help with specialized glazing for windows. Gordon Aluminum, (itself a former aluminum window manufacturer) provides aluminum extrusions for a variety of purposes. And a handful of companies have specialized in providing processing and coating for the metal parts of the windows (of which Linetec is currently the most active today).

There are also a number of companies in the area that have found success providing accessories for windows. Whether Venetian blinds designed and produced by companies like Window Accessory Company, Inc. (WACI) and Nanik, or hardware out of the foundry of Melron, these provide extra utility to the windows produced by other companies. .

In terms of the windows themselves, some companies have pushed windows beyond the old wood-metal dichotomy to explore other options for materials. Northview Window and Door produces a line of plastic windows in Marathon City, which provide their own set of advantages. Major Industries was established to explore the potential of using fiberglass in buildings, and has found success with their lines of translucent panels.

And of course many of these developments of the last half century made their way into wood windows that established the window industry in Marathon County. Crestline (as part of SNE) and Kolbe & Kolbe integrated many of these same developments in their wood windows as well.

Shifting Away from Standardization

While the trend among window manufacturers in the first half of the century saw companies racing to standardize their products, the second half of the century saw successful companies moving back toward filling custom orders. Just as standardization originally helped spur the creation of recognizable brands, modern companies today are focusing on customized options as a way of setting themselves apart from the competition as well.

Many of the Apogee companies are highly specialized in making windows that are specific to a single project. If you were designing a bank building in Alaska, you would not expect Wausau Window & Wall to create a the same window-wall system that went into a University campus in California or a high-rise condo in Florida. And at the same time, it would not be worth the effort to produce a set of pre-made window-wall panels for such a building until it was ordered.

And Kolbe & Kolbe have found success in the wood window side of things, by producing quality windows that fit a range of needs, rather than churning out large numbers of products as their predecessors had.

^ The digital age has changed the way so much of the process behind manufacturing. Compare the tools used in the Marmet drafting room in the 1940s [left] to the depiction of early Computer Aided Design programs at Window Accessory Company, Inc. (WACI), [right].

The rise of this renewed focus on the needs of the customer has emerged in a large part due to the digital world. Whether the use of automation in window construction, widespread adoption of computer aided design programs in engineering departments, and the increasing prominence of the internet to do everything from reaching customers to sending invoices, the twenty-first century has changed just about every aspect of the window business to some extent or another.

The Window Capital

Clearly, Marathon County has been (and remains) an important place in the window industry. But returning to the central conceit of this exhibit (at least it's title), it begs the question of whether this history of window manufacturing qualifies Marathon County to claim the title of "Window Capital of the World."

Is there another community that has contributed as much to the window industry as Marathon County? If there is, they have never put forth a competing claim to the crown.

A few other places have occasionally sought recognition as the "capital of the world" in window-related items. But whether it is the "director of windows" at the Macy's department store boasting that New York was the window capital of the world (in terms of storefront windows) or California, PA petitioning the Guinness Book of World Records to name it the "window box capital of the world," no other city seems to have laid claim to being "window capital" by virtue of it's legacy of window manufacturing. In any case, there does not appear to be any regulatory group to certify these kind of superlatives nor to judge different communities making competing claims.

One could also claim that there are other industries in Marathon County that might deserve to be the thing we claim to be the capital of. Dairy farming has certainly employed more people. Almost all North American ginseng is grown in Marathon County. A number of industries (paper mills, insurance companies, etc.) have put the names of our communities on the map for people across the world.

But at the end of the day, the whole purpose of claiming to be the capital of anything is to help create an identity for the community. So why not frame the discussion around an industry whose considerable contribution to the community is too often transparent to the wider public?